Heel Spurs and Plantar Fasciitis

A heel spur is a bony growth that pokes out below your back heel bone inside your foot. Heel spurs happen when there’s stress on your foot ligaments. Most people don’t realize they have a heel spur until they seek help for heel pain. Heel spurs can’t be cured. Healthcare providers recommend non-surgical treatments to ease symptoms associated with heel spurs.

Heel Spurs

A heel spur is a bony growth that pokes out below your back heel bone inside your foot. Heel spurs happen when there’s stress on your foot ligaments. Most people don’t realize they have a heel spur until they seek help for heel pain. Heel spurs can’t be cured. Healthcare providers recommend non-surgical treatments to ease symptoms associated with heel spurs.

Overview

What is a heel spur?

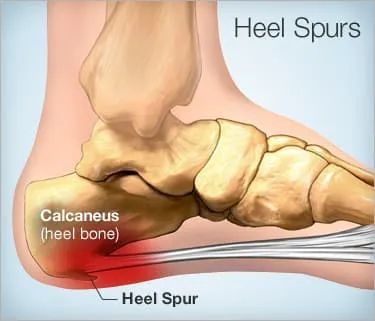

A heel spur or bone spur is a bony growth that pokes out from the bottom of your heel, where your heel bone connects to the ligament running between your heel and the ball of your foot (the plantar fascia). Heel spurs affect about 15% of people.

Heel spurs develop over time. Most people don’t realize they have a heel spur until they seek help for heel pain. While heel spurs can be removed with surgery, healthcare providers recommend non-surgical treatments to ease symptoms associated with heel spurs.

Are heel spurs the same thing as plantar fasciitis?

Heel spurs and plantar fasciitis are related conditions but they’re not the same. Here’s how the two conditions intersect:

- Plantar fasciitis happens when overuse stretches or tears your plantar fascia — the ligament that runs between your heel and the ball of your foot. If you have plantar fasciitis, you’ll probably feel intense stabbing heel pain that comes and goes throughout your day. The pain eases once you walk for a bit but comes back if you sit and then get up to walk some more.

- Heel spurs can happen as a reaction to stress and inflammation caused by plantar fasciitis. Over time your body responds to the stress by building extra bone tissue. This extra tissue becomes a heel spur. Most people don’t feel pain from their heel spur, but when they do, the pain is like plantar fasciitis pain.

Symptoms and Causes

What causes heel spurs?

Heel spurs are your body’s response to stress and strain placed on your foot ligaments and tendons. For example, when you develop plantar fasciitis, your body responds to the stress by creating a heel spur.

About half of all denied claims that are challenged or appealed ultimately end up being covered – but only when policyholders put in the time and energy to fight the denial, the Los Angeles Times

You can also develop heel spurs by repeatedly tearing the covering that lines your heel bone or if you have a gait disorder. (A gait disorder is when an illness or condition affects your balance and coordination so you can’t walk as you usually do.)

Diagnosis and Tests

How do healthcare providers diagnose heel spurs?

Healthcare providers typically examine your foot and ask about physical activity that might have caused your heel pain. Ultimately, X-rays are one of the most common tests that healthcare providers use to diagnose heel spurs.

Management and Treatment

What’s the treatment for heel spurs?

Healthcare providers treat heel spurs the same way they treat plantar fasciitis. That’s because heel pain blamed on heel spurs is actually caused by plantar fasciitis. Treating the symptoms of plantar fasciitis can ease pain associated with heel spurs. Typical treatment includes:

- Resting your heel. If you run or jog, taking a break will help your heel pain.

- Using cold packs or ice. “Icing” the bottom of your foot can help ease heel pain.

- Taking oral anti-inflammatory medicine.

- Wearing footwear or shoe inserts that support your arches and protect your plantar fascia by cushioning the bottom of your foot.

Will I need surgery for my heel spur?

Your heel spur might be removed as part of plantar fasciitis surgery, but healthcare providers rarely perform surgery to remove heel spurs.

Do heel spurs go away without surgery?

Once formed, heel spurs are permanent. Surgery is the only way to remove a heel spur. Since heel spurs usually don’t hurt, treating the condition that caused your heel spur should help ease your heel pain.

Care at Cleveland Clinic

- Bone Spurs Treatment

- Find a Doctor and Specialists

- Make an Appointment

Prevention

What are risk factors for heel spurs?

Several factors increase your risk of developing heel spurs. Some factors are things you can change right away or change over time. Others you cannot change.

Changes you can make right now

- If you jog or run, choose soft surfaces like grass and tracks over hard surfaces like sidewalks and pavement.

- Wear shoes that fit and support your arches.

- Wear slippers or shoes if you walk on hardwood or tile floors.

- Adjust the way you walk so there’s less pressure on your heels.

Changes you can make over time

- Lose weight so you put less pressure on your foot.

- Change your daily routine so you aren’t on your feet as much.

Things you can’t change

- As you age, your plantar fascia becomes less flexible, more prone to damage, and more likely to develop plantar fasciitis.

- You gradually lose the natural fat pad cushions on the bottom of your feet.

- You have fat feet or high arches.

Outlook / Prognosis

What can I expect if I have heel spurs?

Other conditions usually cause heel spurs. There are treatments that can ease the pain of these underlying conditions, but surgery is the only way to remove a heel spur. Ask your healthcare provider if surgery is an appropriate solution to your heel spur problem.

Living With

How do I take care of myself if I have heel spurs?

Once you have a heel spur, you’ll always have a heel spur. Fortunately, heel spurs generally don’t hurt. But you should plan on managing the symptoms associated with heel spurs. Here are some steps you can take:

- Cut back on activities that make your heel pain worse.

- Be sure you have well-fitting shoes that support your arches.

When should I see my healthcare provider?

Talk to your provider if treatment for your heel pain doesn’t seem to help. While heel spurs don’t always hurt, ongoing heel pain might be a sign that it’s time to try other treatments or check for other potential problems.

What questions should I ask my doctor?

- Why do I have a heel spur?

- What can you do for my heel spur?

- Will my heel spur go away?

- If my heel spur isn’t causing my heel pain, what is?

- What treatments can address the problem that caused my heel spur?

A note from Cleveland Clinic

A heel spur happens when stress and strain damage your plantar fascia, the ligament on the bottom of your foot. Heel spurs usually aren’t the reason why your heel hurts. You probably learned about your heel spur when you sought help for heel pain. Even if your heel spur didn’t cause your heel pain, you should still pay attention to your heels. If your heels hurt when you do certain activities, talk to your healthcare provider about additional steps you can take to ease your heel pain.

Heel Spurs and Plantar Fasciitis

A heel spur is a calcium deposit causing a bony protrusion on the underside of the heel bone. On an X-ray, a heel spur can extend forward by as much as a half-inch. Without visible X-ray evidence, the condition is sometimes known as “heel spur syndrome.”

Although heel spurs are often painless, they can cause heel pain. They are frequently associated with plantar fasciitis, a painful inflammation of the fibrous band of connective tissue (plantar fascia) that runs along the bottom of the foot and connects the heel bone to the ball of the foot.

Treatments for heel spurs and associated conditions include exercise, custom-made orthotics, anti-inflammatory medications, and cortisone injections. If conservative treatments fail, surgery may be necessary.

Causes of Heel Spurs

Heel spurs occur when calcium deposits build up on the underside of the heel bone, a process that usually occurs over a period of many months. Heel spurs are often caused by strains on foot muscles and ligaments, stretching of the plantar fascia, and repeated tearing of the membrane that covers the heel bone. Heel spurs are especially common among athletes whose activities include large amounts of running and jumping.

Risk factors for heel spurs include:

- Walking gait abnormalities,which place excessive stress on the heel bone, ligaments, and nerves near the heel

- Running or jogging, especially on hard surfaces

- Poorly fitted or badly worn shoes, especially those lacking appropriate arch support

- Excess weight and obesity

Other risk factors associated with plantar fasciitis include:

- Increasing age, which decreases plantar fascia flexibility and thins the heel’s protective fat pad

- Diabetes

- Spending most of the day on one’s feet

- Frequent short bursts of physical activity

- Having either flat feet or high arches

Symptoms of Heel Spurs

Heel spurs often cause no symptoms. But heel spurs can be associated with intermittent or chronic pain — especially while walking, jogging, or running — if inflammation develops at the point of the spur formation. In general, the cause of the pain is not the heel spur itself but the soft-tissue injury associated with it.

Many people describe the pain of heel spurs and plantar fasciitis as a knife or pin sticking into the bottom of their feet when they first stand up in the morning — a pain that later turns into a dull ache. They often complain that the sharp pain returns after they stand up after sitting for a prolonged period of time.

Non-Surgical Treatments for Heel Spurs

The heel pain associated with heel spurs and plantar fasciitis may not respond well to rest. If you walk after a night’s sleep, the pain may feel worse as the plantar fascia suddenly elongates, which stretches and pulls on the heel. The pain often decreases the more you walk. But you may feel a recurrence of pain after either prolonged rest or extensive walking.

If you have heel pain that persists for more than one month, consult a health care provider. They may recommend conservative treatments such as:

- Stretching exercises

- Shoe recommendations

- Taping or strapping to rest stressed muscles and tendons

- Shoe inserts or orthotic devices

- Physical therapy

- Night splints

Heel pain may respond to treatment with over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), ibuprofen (Advil), or naproxen (Aleve). In many cases, a functional orthotic device can correct the causes of heel and arch pain such as biomechanical imbalances. In some cases, injection with a corticosteroid may be done to relieve inflammation in the area.

Surgery for Heel Spurs

More than 90 percent of people get better with nonsurgical treatments. If conservative treatment fails to treat symptoms of heel spurs after a period of 9 to 12 months, surgery may be necessary to relieve pain and restore mobility. Surgical techniques include:

- Release of the plantar fascia

- Removal of a spur

Pre-surgical tests or exams are required to identify optimal candidates, and it’s important to observe post-surgical recommendations concerning rest, ice, compression, elevation of the foot, and when to place weight on the operated foot. In some cases, it may be necessary for patients to use bandages, splints, casts, surgical shoes, crutches, or canes after surgery. Possible complications of heel surgery include nerve pain, recurrent heel pain, permanent numbness of the area, infection, and scarring. In addition, with plantar fascia release, there is risk of instability, foot cramps, stress fracture, and tendinitis.

Prevention of Heel Spurs

You can prevent heel spurs by wearing well-fitting shoes with shock-absorbent soles, rigid shanks, and supportive heel counters; choosing appropriate shoes for each physical activity; warming up and doing stretching exercises before each activity; and pacing yourself during the activities.

Avoid wearing shoes with excessive wear on the heels and soles. If you are overweight, losing weight may also help prevent heel spurs.

Show Sources

SOURCES:

American Podiatric Medical Association: “Heel Pain,” “General Foot Health.”

American Academy of Podiatric Sports Medicine: “Running and Your Feet.”

American Podiatric Medical Association: “Rearfoot Surgery.”

FamilyDoctor.org: “Plantar Fasciitis: “A Common Cause of Heel Pain.”

Green, D. Podiatry Today, May 2006.

DeLee: DeLee and Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, 3rd ed.

The Nemours Foundation.

An Overview of Heel Spurs

Jonathan Cluett, MD, is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon with subspecialty training in sports medicine and arthroscopic surgery.

Updated on October 29, 2021

Stuart Hershman, MD, is a board-certified spine surgeon. He specializes in spinal deformity and complex spinal reconstruction.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

A heel spur (also known as a calcaneal spur) is a bony outgrowth that you can sometimes see and feel on the underside of your foot. It is made up of calcium deposits and can have a pointy, hooked, or shelf-like shape. There are several causes of heel spurs, but they very often occur in patients with plantar fasciitis, or the inflammation of the plantar fascia—the tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot and connects the heel to the toes.

Many people think that heel spurs cause heel pain—but that’s not always the case. According to the Cleveland Clinic, one out of 10 people have heel spurs, but only one out of 20 people with a heel spur experiences heel pain. Others may experience symptoms that include tenderness, a dull ache, or sharp pain when standing.

Symptoms

Most often, it’s not the heel spur that causes the pain, but the inflammation and irritation of the plantar fascia. Heel pain is worst in the morning after sleep (some people say it feels like a knife going into the heel), making it difficult to take those first steps out of bed.

This is because the foot is resting in plantar flexion overnight (i.e., your toes are pointed down), which causes the fascia to tighten. As you put pressure on the foot, the fascia stretches, which causes pain. This does subside as you begin to move and loosen the fascia (although you will likely still feel a dull ache), only to return after walking or standing for extended periods.

Other symptoms of heel spurs include:

- A small, visible protrusion: On X-rays, a heel spur can be up to a half-inch long.

- Inflammation and swelling

- Burning, hot sensation

- Tenderness that makes it painful to walk barefoot

Causes

Heel spurs occur in 70 percent of patients with plantar fasciitis. The plantar fascia is one of the major transmitters of weight across the foot as you walk or run. When the plantar fascia becomes inflamed, a heel spur can form at the point between the fascia (the tissue that forms the arch of the foot) and the heel bone.

Most common among women, heel spurs can also be related to another underlying condition, including osteoarthritis, reactive arthritis (Reiter’s disease), and ankylosing spondylitis.

Other causes of heel spurs include:

- Overuse: Activities like running and jumping, especially if done on hard surfaces, can cause heel spurs by wearing down the heel and arch of the foot.

- Obesity: The more weight you carry around, the greater your risk of heel spurs.

- Improper footwear: Ill-fitting or non-supportive footwear (like flip-flops) can cause heel spurs.

Diagnosis

Your healthcare professional may ask about your history of heel pain and examine your foot for tenderness at the bottom of the foot, near the heel. She may ask you to flex your foot to assess pain and range of motion. She will also visually examine the heel looking for a protrusion, which may or may not be present.

A heel spur diagnosis is formally made when an X-ray shows the bony protrusion from the bottom of the foot at the point where the plantar fascia is attached to the heel bone.

Treatment

By and large, the treatment of heel spurs is the same as that of plantar fasciitis, with the first step being short-term rest and inflammation control.

For the majority of people, heel spurs do get better with conservative treatment that may include:

- Rest

- Icing

- Anti-inflammatory medication

- Stretching

- Orthotics

- Physical therapy

The heel spur will not go away with these treatments, but the discomfort it causes can usually be sufficiently controlled with their use.

When that’s not the case, cortisone injections may be helpful in some individuals. Surgery to remove the heel spur is rare and only necessary when the trial of (and dedication to) the above treatments have failed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the symptoms of a heel spur?

Heel spur symptoms can include heel pain that is worst in the morning when waking up, inflammation, swelling, a burning or hot sensation, tenderness, and a small, visible protrusion in the heel. Only 50% of people with a heel spur feel pain from it. If you have heel pain, it’s a good idea to speak with a healthcare provider to find the cause.

What causes a heel spur?

A heel spur is a common occurrence in people with plantar fasciitis, a condition that causes sharp or dull pain at the bottom of the heel. Underlying conditions such as osteoarthritis, reactive arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis can also cause a heel spur to form. Other causes include heel overuse, obesity, and ill-fitting footwear.

How can I treat a heel spur?

There are a few different methods to treat a heel spur. These include getting plenty of rest, pressing a covered ice pack against the area, using an anti-inflammatory medication, stretching, wearing orthotics (shoe inserts to decrease foot pain), and physical therapy.

Verywell Health uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy.

- Ahmad J, Karim A, Daniel JN. Relationship and Classification of Plantar Heel Spurs in Patients With Plantar Fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(9):994-1000. doi:10.1177/1071100716649925

- Krukowska J, Wrona J, Sienkiewicz M, Czernicki J. A comparative analysis of analgesic efficacy of ultrasound and shock wave therapy in the treatment of patients with inflammation of the attachment of the plantar fascia in the course of calcaneal spurs. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(9):1289-1296. doi:10.1007/s00402-016-2503-z

- Kirkpatrick J, Yassaie O, Mirjalili SA. The plantar calcaneal spur: a review of anatomy, histology, etiology and key associations. J Anat. 2017;230(6):743-751. doi:10.1111/joa.12607

- Alatassi R, Alajlan A, Almalki T. Bizarre calcaneal spur: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;49:37-39. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.06.006

- Boules M, Batayyah E, Froylich D, et al. Effect of Surgical Weight Loss on Plantar Fasciitis and Health-Care Use. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2018;108(6):442-448. doi:10.7547/15-169

- Agyekum EK, Ma K. Heel pain: A systematic review. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18(3):164-9. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2015.03.002

- Cleveland Clinic. 6 reasons you shouldn’t assume foot pain is a heel spur. November 13, 2019.

Additional Reading

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. “Plantar Fasciitis and Bone Spurs.” https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/plantar-fasciitis-and-bone-spurs.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Think You Have a Heel Spur? It’s Probably Plantar Fasciitis.” https://health.clevelandclinic.org/think-heel-spur-probably-plantar-fasciitis.

- Johal KS, Milner SA. “Plantar Fasciitis and the Calcaneal Spur: Fact or Fiction?” Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2012;18(1):39-41. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2011.03.003.

By Jonathan Cluett, MD

Jonathan Cluett, MD, is board-certified in orthopedic surgery. He served as assistant team physician to Chivas USA (Major League Soccer) and the United States men’s and women’s national soccer teams.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/463670463-56a6d94a3df78cf772908b2f.jpg)