How to Lower Your A1c: The Complete Guide

Also called the Diabetes Plate Method, the idea here is to simplify your mealtime calculations while eating the right foods in the right proportions. Picture a plate that’s less than a foot in diameter and divide it up into quarters:

9 Ways to Lower Your A1C Level

Diabetes is a serious, chronic condition that can lead to many complications. But there are ways to manage your condition.

Getting your A1C level tested, especially if you’re at risk for developing type 2 diabetes, is a good way of taking care of yourself. An early diagnosis helps you get treatment before complications can occur.

You can lower your A1C by making changes to your:

- exercise regimen

- diet

- medication

If you already have diabetes and are taking medications that can cause low blood sugar levels, find out your optimal levels.

Here are nine ways to lower your A1C:

Americans see their primary care doctors less often than they did a decade ago. Adults under 65 made nearly 25% fewer visits to primary care providers in 2016 than they did in 2018, according to National Public Radio. In the same time period, the number of adults who went at least a year without visiting a primary care provider increased from 38% to 46%.

1. Make a food plan

Eating the right foods is essential to lowering your A1C, so you want to make a plan and stick to it. There are a few important strategies for this:

- Make a grocery list. When you’re trying to fill your basket with nutrient-dense foods while minimizing sweets, having and following a list can help you avoid impulse purchases. And if you’re trying out new recipes, your list can help make sure you get home with all the right ingredients.

- Meal prep ahead of time. When you’re fixing a nutritious meal, you can save time by doubling the recipe, so you have another meal readily available later in the week.

- Build in flexibility. Plan to give yourself options before you need them, so you’re not scrounging for a fallback when the cupboards are bare and your stomach is rumbling.

2. Measure portion sizes

It’s important to choose not just the right foods to lower your A1C but also the right amount. Here are a few tips to avoid overdoing it:

- Get familiar with the appropriate portion sizes. You don’t have to measure every food you eat by the gram to learn to recognize and make a habit of thinking about what’s a right-size portion and what’s too much.

- Use smaller plates at home. It’s not uncommon to want to fill your plate in the kitchen, but for portioning purposes, it might help for the plate to be smaller.

- Avoid eating from a bag. In the interest of mindful munching, if you’re having a few crackers, pull out a reasonable serving, then put the rest back in the cupboard for later.

- Be mindful when going out to eat. Rather than order an entrée that’s more food than you need, you may want to ask a friend if they’ll split something with you. Or you can plan to take half home to eat later in the week.

3. Track carbs

The appropriate amount of carbohydrates varies from person to person and is worth discussing with your doctor, but in general, carbs are easy to overdo if you’re not keeping track. It can be helpful to maintain a food diary or use an app to keep track of your carb intake.

Starting out, you may have to take some time looking at nutrition labels, but with practice, this will become a quick and easy process and will help you get a sense of which foods are most carb-heavy so you can adjust accordingly.

4. Plate method

Also called the Diabetes Plate Method, the idea here is to simplify your mealtime calculations while eating the right foods in the right proportions. Picture a plate that’s less than a foot in diameter and divide it up into quarters:

- Half of what’s on the plate — that is, two quarters — should be low carb vegetables. There are many to choose from, including broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, peppers, mushrooms, cucumber, and anything leafy, like lettuce, cabbage, spinach, and so on.

- The next quarter of the plate should be lean proteins, which include fish, chicken, eggs, shellfish, cheese, tofu, and lean cuts of pork or beef.

- The last quarter of the plate goes to carbs, including grains like rice and whole grain bread, as well as fruit and starchy vegetables like potatoes.

With practice, you can apply the same proportions and ideas behind the plate method to foods that don’t lend themselves to being divided across a plate like sandwiches, for instance.

5. Have a realistic weight loss goal

Set yourself up for success. It’s important to be practical because a slow, steady approach to weight loss ( a pound or two a week , at most) tends to get the best results when it comes to keeping weight off.

It’s also worth noting the results don’t have to be drastic to meaningfully improve your health. Experts say even 5 percent can make a difference. This means if someone at 180 pounds adjusts their exercise and food habits and works their way down to 170 over a few months, the resulting health benefits can be worthwhile.

Talk with your doctor about what weight loss goal makes sense for you and how best to work toward it.

6. Exercise plan

Increase your activity level to get your A1C level down for good. Start with a 20-minute walk after lunch. Build up to 150 minutes of extra activity a week.

Get confirmation from your doctor first before you increase your activity level. Being active is a key part of reducing the risk of developing diabetes.

Remember: Any exercise is better than no exercise. Even getting up for 2 minutes every hour has been shown to help reduce the risk of diabetes.

7. Take medications

The medications that lower fasting blood sugars will also lower your A1C level. Some medications primarily affect your blood sugars after a meal, which are also called postprandial blood sugars.

These medications include sitagliptin (Januvia), repaglinide (Prandin), and others. While these medications don’t significantly improve fasting glucose values, they still help lower your A1C level because of the decrease in post-meal glucose spikes.

8. Supplements and vitamins

It’s worth talking with your doctor about supplements you might take to improve your A1C level. Some of those to consider include aloe vera and chromium. Aloe vera is a succulent that may inhibit the body’s absorption of carbohydrates. A 2016 review of studies found that it may lower A1C levels by around 1 percent .

A 2014 analysis of prior studies suggests chromium, a mineral found in vegetables like potatoes and mushrooms, as well as oysters, can lower A1C by more than half a percent in people with type 2 diabetes.

However, a 2002 review of previous research found that chromium had no impact on glycemic control in those who do not have diabetes.

9. Stay consistent

Lowering your A1C levels depends on making changes that become habits. The best way to make something second nature is to keep doing it consistently, so your week-long streak turns into a month and so on.

Particularly where eating patterns and exercise are concerned, slow, steady progress tends to deliver the best long-term results.

Sugar from food makes its way into your bloodstream and attaches to your red blood cells — specifically to a protein called hemoglobin.

Your A1C level is a measure of how much sugar is attached to your red blood cells. This can help determine if you have diabetes or prediabetes and can help inform how best to manage it.

The A1C test is a blood test that screens for diabetes. If you have diabetes, it shows whether treatment is working and how well you’re managing the condition. The test provides information about a person’s average levels of blood sugar over a 2- to 3-month period before the test.

The number is reported as a percentage. If the percentage is higher, so are your average blood glucose levels. This means your risk for either diabetes or related complications is higher.

Although A1C is the gold standard of diabetes diagnosis, keep in mind that it’s not always accurate. Many clinical conditions can affect A1C, including iron deficiency anemia and other blood disorders that affect red blood cells.

A1C is one of the primary tests used for diabetes diagnosis and management. It can test for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but not for gestational diabetes. The A1C test can also predict the likelihood that someone will develop diabetes.

The A1C test measures how much glucose (sugar) is attached to hemoglobin. This is the protein in red blood cells. The more glucose attached, the higher the A1C.

The A1C test is groundbreaking because :

- It doesn’t require fasting.

- It gives a picture of blood sugar levels over a period of weeks to months instead of at just one time, like fasting sugars.

- It can be done at any time of day. This makes it easier for doctors to give and make accurate diagnoses.

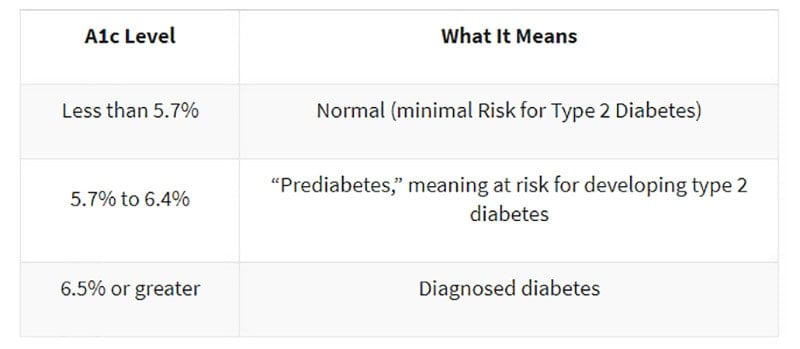

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, an optimal A1C is below 5.7 percent . If your score is between 5.7 and 6.4 percent, the diagnosis is prediabetes.

Having prediabetes puts you at risk for developing type 2 diabetes within 10 years. But you can take steps to prevent or delay developing diabetes. If you test positive for prediabetes, it’s best to get retested every year.

There’s an increased chance of prediabetes developing into type 2 diabetes if your A1C is 6.5 percent or higher.

If you have been diagnosed with diabetes, keeping your A1C levels below 7 percent can help reduce the risk of complications.

If you receive a diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes, your doctor may prescribe a home monitor to allow you to test your blood sugar. Be sure to talk with your doctor to learn what to do if the results are too high or too low for you.

It’s important to talk with your doctor about what steps you can take to help lower your A1C levels. They can help you set and monitor practical goals and may also prescribe medication.

Additionally, your doctor may connect you with a dietician who can help you better understand the nutrition component of lowering your A1C levels, as well as determine the best ways to adjust your diet and habits around food in health-promoting, practical ways.

Last medically reviewed on August 20, 2021

How we reviewed this article:

Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy.

- All about your A1C. (2021).

cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/managing-blood-sugar/a1c.html - The A1C test & diabetes. (2018).

niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/tests-diagnosis/A1C-test - Basic report: 9326, Watermelon, raw. (2018).

fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/167765/nutrients - Carb counting and diabetes. (n.d.).

diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/what-can-i-eat/understanding-carbohydrates/carbohydrate-counting.html - Endoscopic Weight Loss Program: Diabetes. (n.d.).

hopkinsmedicine.org/digestive_weight_loss_center/conditions/diabetes.html - Evert A, et al. (2019). Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: A consensus report.

care.diabetesjournals.org/content/42/5/731 - Fats. (n.d.).

diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/what-can-i-eat/making-healthy-food-choices/fats-and-diabetes.html - Gregor M. (2015). Lipotoxicity: How saturated fat raises blood sugar.

nutritionfacts.org/video/lipotoxicity-how-saturated-fat-raises-blood-sugar/ - Helping the student with diabetes succeed. (2020.).

niddk.nih.gov/health-information/communication-programs/ndep/health-professionals/helping-student-diabetes-succeed-guide-school-personnel/tools-for-effective-diabetes-management - Losing weight. (2020).

cdc.gov/healthyweight/losing_weight/index.html - McKennon SA. (2018). Non-pharmaceutical intervention options for type 2 diabetes: Diets and dietary supplements (botanicals, antioxidants, and minerals).

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279062/#non-phrma-intrvn-t2d.toc-insulin-sensitizers - National diabetes statistics report. (2020).

cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html - Oliveira R. (2016). Diet and diabetes: Why saturated fats are the real enemy.

ucdintegrativemedicine.com/2016/09/diet-diabetes-saturated-fats-real-enemy/#gs.AkO4OPQ - Serving and portion sizes: How much should I eat? (2019).

nia.nih.gov/health/serving-and-portion-sizes-how-much-should-i-eat - What is the diabetes plate method? (2020).

diabetesfoodhub.org/articles/what-is-the-diabetes-plate-method.html - Your game plan to prevent type 2 diabetes. (2017).

niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-type-2-diabetes/game-plan

Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available.

How to Lower Your A1c: The Complete Guide

We are always told that having a low A1c is an important goal in our diabetes management, but do you know why? Do you know what a good A1c target is, how to lower your A1c, and how quickly you can lower your A1c safely?

These are the questions I will answer in this comprehensive guide on what A1c is, how to lower your A1c, and why achieving a low A1c isn’t the only (or necessarily the best) goal when it comes to diabetes management.

Table of Contents

What is A1c?

A1c, hemoglobin A1c, HbA1c or glycohemoglobin test (all different names for the same thing) is a blood test that measures your average blood sugar over the last 2-3 months. It’s not an “even average,” but an average where your blood sugars over the last few weeks count a little more than your blood sugars 2-3 months ago.

“The A1c test is based on the attachment of glucose to hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. In the body, red blood cells are constantly forming and dying, but typically they live for about three months. Thus, the A1c test reflects the average of a person’s blood glucose levels over the past three months. The A1c test result is reported as a percentage. The higher the percentage, the higher a person’s blood glucose levels have been. A normal A1c level is below 5.7 percent.”

It’s important to note here that the term “normal A1c level” in this context refers to people without diabetes. I will get back to what a “normal A1c level” is for people living with diabetes below.

How to test your A1c

Your doctor or endocrinologist should test your A1c regularly (typically every 3-6 months). The doctor simply pricks your finger (or ear if you prefer) and takes a tiny blood sample. If the doctor’s office has an A1c kit, you should get your result before your consultation is over.

You can also buy home A1c kits (no prescription required) and do the test yourself. Home A1c kits can be useful if you go for more than three months between doctor visits and want to keep an eye on how your A1c is developing yourself.

The home kits are generally accurate within plus/minus 0.5 percentage points, which is more than good enough to give you a trustworthy result. The downside of the home kits is that they require a larger amount of blood (four large drops) than a regular blood sugar test, and if you don’t apply enough blood, you’ll get an error message and will have lost a test strip.

You can find home test kits on Amazon and in some pharmacies.

Why you should care about your A1c

Multiple studies have shown that high average blood sugars increase the risk of diabetes-related complications. Lowering your A1c to the recommended range will reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications significantly:

- Eye disease risk is reduced by 76%

- Kidney disease risk is reduced by 50%

- Nerve disease risk is reduced by 60%

- Any cardiovascular disease event risk is reduced by 42%

- Nonfatal heart attack, stroke, or risk of death from cardiovascular causes is reduced by 57%

Achieving an A1c in the recommended range is, therefore, one of the most important things you can do to improve your long-term health when you live with diabetes.

However, the closer you get to the recommended A1c target, the less benefit you will get from lowering your A1c further. Taking your A1c from 12% to 11% makes a big difference while lowering your A1c from 7% to 6% provides a much smaller benefit. In fact, lowering your A1c too much may not be a good idea if it means that you increase how often you experience hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

I will explain why “time-in-range” is just as important as a low A1c later in this guide.

What is a “normal” A1c?

Now that you have your A1c number, let’s look at what that number actually tells you. The American Diabetes Association has established the following guidelines:

This does NOT mean that you need an A1c of less than 5.7% if you’re living with diabetes. It means that if you do NOT live with diabetes, your A1c is expected to be below 5.7%. There are different recommendations for what an appropriate A1c is for people living with diabetes.

I had a chance to asked Dr. Anne Peters, MD, Director, USC Clinical Diabetes Program and Professor of Clinical Medicine Keck School of Medicine of USC as well as Gary Scheiner, MS, CDE, owner and Clinical Director of Integrated Diabetes Services and author of Think Like a Pancreas, what their perspectives are on a good A1c target:

Gary Scheiner, MS, CDE:

“A1c goals should be individualized based on the individual capabilities, risks, and prior experiences. For example, we generally aim for very tight A1c levels during pregnancy and more conservative targets in young children and the elderly. Someone with significant hypoglycemia unawareness and a history of severe lows should target a higher A1c than someone who can detect and manage their lows more effectively. And certainly, someone who has been running A1c’s in double digits for quite some time should not be targeting an A1c of 6%… better to set modest, realistic, achievable goals.”

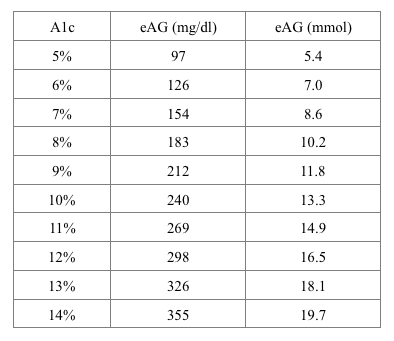

In their Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, the American Diabetes Association recommends an A1c target of below 7% for adults living with diabetes. An A1c of 7% roughly translates to an average blood sugar of 154 mg/dl (8.6 mmol/L) as you can see from this conversion chart.

To learn more about blood sugar levels, please read “What are Normal Blood Sugar Levels“.

A1c vs. Time-in-Range

A1c has long been considered the best measure of diabetes management because it was the most accurate tool to observe long-term blood sugar trends. This has changed with the introduction of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM). By using a CGM, you can now get a very accurate picture of not only your average blood sugar, but your blood sugar fluctuations as well.

This makes it possible to track another key component of diabetes management: Time-in-Range.

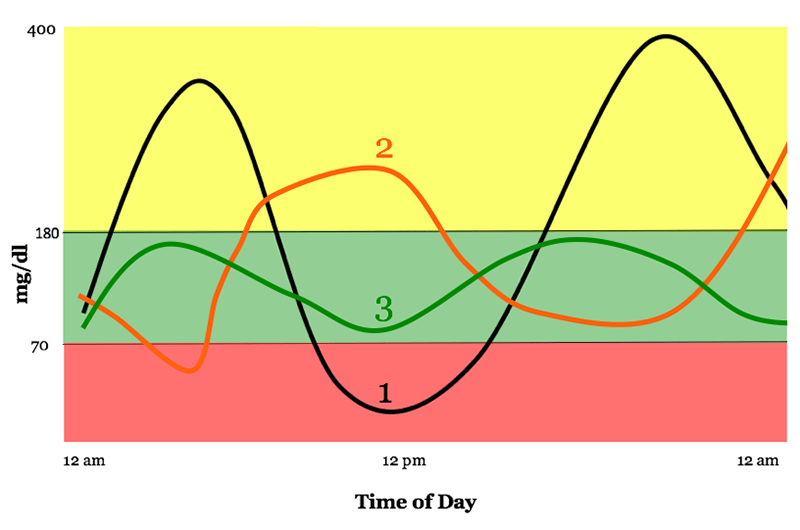

Time-in-range refers to the percentage of time in which your blood sugar is within a specific range. To see why time-in-range is important, take a look at the three lines in the graph below. All three lines show an average blood sugar of about 154 mg/dl (which equals an A1c of about 7%) but with very different fluctuations. I think we would all prefer our blood sugar to follow line 3 rather than line 1.

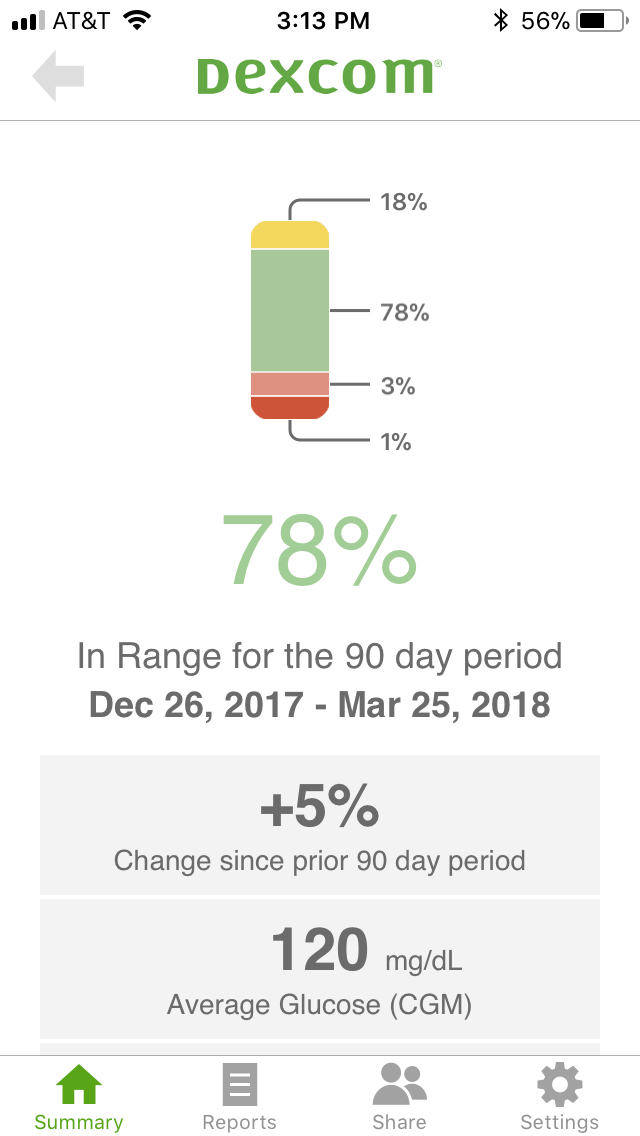

Graph used with permission from Diatribe

Some guidelines state that your blood sugar range should be set to 70-180 mg/dl (3.9-10 mmol/l), but you may find that to be too large or small of a range for you. According to this interview with several diabetes experts, most recommend that you spend less than 3% of the time below 70 mg/dl (3.9 mmol/l) and less than 1% of the time below 53 mg/dl (3 mmol/l). However, they also agree that the actual time spent in range needs to be individualized.

On average, the experts didn’t expect the general diabetes population to be in range more than 50% of the time at most, so talking about incremental improvement probably makes more sense than setting a fixed number.

How to measure Time-in-Range

If you wear a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM), your time-in-range should be listed when you download your data (as in the example from a Dexcom CGM below). If you don’t use a CGM, all you can do is look at your manual blood sugar tests and pay attention to your amount of high and low blood sugars. What’s an acceptable high and low is something you have to discuss with your medical team.

What is more important: a low A1c or a high Time-in-Range?

Optimally, you’d have an A1c below 7% accompanied by a low blood sugar variance (high time-in-range). A good general guideline is:

- The higher your A1c, the more important it is to focus on getting it down.

- The lower your A1c, the more important time-in-range becomes.

If your A1c is below 6-7%, focusing on increasing your time-in-range will probably have a larger positive health impact than lowering your A1c further.

So is A1c a bad way to gauge whether your diabetes management is on track? Not necessarily, but to quote Gary Scheiner, MS, CDE:

“I’ve never been a huge fan of using A1c to gauge the “quality” of a person’s glucose control, simply because it represents an average… and an average can reflect lots of highs and lows rather than time spent within one’s target range. However, it’s not something we can ignore either since there is a correlation between A1c and the risk of long-term complications.”

Can your A1c be too low?

As described above, the answer to this question depends almost entirely on how often you experience hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). If you (almost) never experience hypoglycemia, your A1c technically cannot be too low. Some people achieve A1c levels below 5% by following a very strict diabetes management and diet regimen and have almost no blood sugar fluctuations.

HOWEVER, if you often experience hypoglycemia, that will result in an “artificial” low A1c reading because your hypoglycemia events are lowering your blood sugar average. In that case, focusing on increasing time-in-range is much more important than further lowering your A1c. In fact, you may even benefit from a slightly higher A1c with fewer blood sugar fluctuations.

It’s also important to note that lowering your A1c below the recommended range of 6-7% hasn’t been proven to provide any health benefits. Therefore, a very low A1c shouldn’t be a goal in itself.

How to lower your A1c

Now that you have a thorough understanding of A1c and time-in-range, as well as why looking at your A1c in isolation isn’t optimal, the obvious question is:

How do you lower your A1c while improving or sustaining your time-in-range?

I will cover the four most important things you can do below but it’s always recommended that you start by having a conversation with your medical team before making changes to your diabetes management.

Identify the main “pain points”

Whether you are self-managing your diabetes or work closely with your medical team, the first step should always be to try to identify the main “pain points” or reasons why your A1c is higher than you’d like. The only real way of doing this is by tracking your blood sugars very closely.

If you wear a Continuous Glucose Monitor, you can look at your 7-day, 30-day, and 90-day data to see if you can spot any trends. For example, you might find that you are running high from 1-5 AM every night, every morning (hello Dawn Phenomenon) or every day after meals. Or perhaps you always go low after exercise. We all have different blood sugar patterns.

It’s also very possible that you simply are running your blood sugar a little too high all the time and could benefit from adjusting your diabetes medication. Identifying patterns like that makes it possible to pinpoint areas of potential improvement so you can start making a plan for how to limit your high and low blood sugars.

If you rely on manual blood sugar testing, it’s a little trickier since most people don’t test every five minutes. What I would recommend is increasing how often you test for a while, and maybe even test during the night if you wake up anyway. Most meters allow you to download data to your computer, or you can upload the data to app-based platforms like One Drop or mySugr. This can help you see the data in a more cohesive way so you can start looking for trends.

Create a plan for your diabetes management

Now that you have a better idea of what your “pain points” are, you can start making changes to your diabetes management.

Your doctor may suggest a different medication regime. For example, some people (regardless of their type of diabetes) are prescribed Metformin to help with Dawn Phenomenon (morning blood sugar spikes not related to eating). Others may need adjustments to insulin dosing, etc.

If you’re insulin-dependent and consistently have high blood sugars in the morning, getting your blood sugar fluctuations and A1c down might be as simple as adjusting your nighttime basal insulin. Or, if you run high every day after meals, your carb-to-insulin ratio might be off, and adjusting that could be what sets you on a path of a lower A1c. Until you collect the data and do the analysis, you have no way of knowing this.

I want to make an important point here: increasing your diabetes medication is not a sign of failure! It’s often the best (and sometimes only) way to control your blood sugar and bring down your A1c.

I adjust my insulin up and down all the time when I change my diet or exercise routine. Adjusting your medication is an important tool in your diabetes toolbox and something you should always discuss with your medical team.

Understand nutrition and adjust your diet

What you choose to eat and drink can have a major impact on not only your waistline, mood, and well-being, but also on your blood sugar levels.

All macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) can affect your blood sugar to some degree so developing a good understanding of how they affect your blood sugar will enable you to be proactive and prevent blood sugar swings.

Carbohydrates (carbs)

Carbohydrates have the greatest impact on your blood sugar, which is why many people with diabetes can benefit from following a low- to medium-carb diet (or even a ketogenic diet). The fewer carbs you eat, the less insulin you need to take, which makes diabetes management easier.

However, you don’t have to follow a low-carb diet if it doesn’t work for you – physically or mentally. As I wrote in my post about which diet is best for people with diabetes, it is very possible to have great blood sugar control on a medium (or even high) carb diet, as long as you experiment, take notes, and learn to take the right amounts of insulin for the carbs you are eating.

It is very important to realize that we all react differently to carbs so you have to find the diet and foods that are right for you.

As an example, people react very differently to carbs like oats or sweet potato. Some people can eat oats with only a small increase in blood sugar while others see a quick spike. By simply knowing this, people struggling with a certain type of carb can choose to reduce their consumption or cut it out of their diet altogether.

Protein & fats

While carbs affect blood sugar most significantly, protein and fat also have an impact. Some, like Dr. Sheri Colberg, even think that simply looking at carbs when estimating blood sugar impact (and dosing insulin) is an outdated and inefficient way to perceive diabetes management and that you should focus more on total calories (read more here).

The key thing to be aware of is that when protein and especially fat is consumed with carbohydrates, the energy from the meal will be released more slowly, which means that your blood sugars will be impacted more slowly as well.

While I don’t believe your diabetes management should completely dictate how you live your life and which diet you choose to follow, it can be worth evaluating what food choices make life easier for you. By making a conscious choice of which type of nutrition plan to follow (the majority of the time), you can more easily establish healthy habits that will benefit not only your overall health but also your daily blood sugar levels, and thereby your A1c.

Increase activity (exercise)

While exercise is essential for building and maintaining good health and improving insulin sensitivity, it can be a double-edged sword if it constantly throws your blood sugars for a loop. Not only is that very frustrating, scary, and annoying, but it can also affect your A1c and time-in-range negatively.

The key is to understand how different types of exercise affect blood sugars and, if you use insulin, learn your formula for insulin and food around workouts.

Cardio

Cardio, such as brisk walking, jogging, swimming, biking, or dancing, are all excellent types of exercise, and as little as 20-30 minutes a day can make a significant difference when it comes to improving insulin resistance and managing blood sugar levels.

Not only does exercise reduce blood glucose during exercise, but it also improves your insulin sensitivity for hours after your workout, meaning that you need less insulin.

If you treat your diabetes with insulin, you will have to manage your insulin levels so you don’t experience exercise-induced hypoglycemia. This comes down to reducing your insulin significantly or consuming carbs before your workout.

In general, it should not be needed to “carb up” to do up to 60 minutes of steady-state cardio, but there can be situations where reducing insulin before exercise can’t be done, so additional carbohydrates must be consumed.

Resistance training

Adding resistance training to your daily routine, even if it’s just bodyweight exercise, can be instrumental in increasing your insulin sensitivity and lowering your A1c.

Whereas cardio will lower blood sugar during exercise and potentially up to 36 hours after exercise, resistance training can increase insulin sensitivity for much longer since muscles work as little “glucose tanks” and you’ll store more glucose in your muscles rather than sending it directly to your bloodstream. The more muscles you have, the better your insulin sensitivity.

Just be aware that most people will see an increase in blood sugars during resistance training (research was mainly done on people living with type 1 diabetes) rather than a decrease. The reason for the increase in blood sugar is that the improved insulin sensitivity from exercising is surpassed by your body’s increased glucose production. Your body is producing glucose faster than you can use it!

For a detailed guide to resistance training and diabetes, please see my article “How Resistance Training Affects Your Blood Sugar.”

Because resistance training is so effective at increasing your insulin sensitivity, it’s a great way to lower your blood sugar consistently. If you exercise regularly, the effect of exercising overlaps from one workout to the next and you essentially achieve a permanent increase in insulin sensitivity.

How quickly can you lower your A1c?

Because A1c is simply a measure of your average blood sugar over 2-3 months, it can (in theory) decrease by any amount over that time period. If you, from one day to the next, decreased your daily average blood sugar from 300 mg/dl (16.7 mmol/l) to 120 mg/dl (6.7 mmol/l), your A1c would decrease from 12% to 6% in around two months.

However, it may not be a good idea to lower your A1c so quickly, as I will explain below.

Why you shouldn’t lower your A1c too quickly

It can be a good idea to approach lowering your A1c with a bit of caution. Just as crash dieting isn’t healthy, there can be some serious health risks associated with lowering your A1c too quickly. I turned to Dr. Peters for an explanation:

“If you lower your A1c too quickly, many bad things can happen. First, weight gain and total body swelling. Next, it can cause bleeding in the retina (back of the eyes) which can lead to blindness, and third, it can cause painful neuropathy that never goes away. It’s slightly different for newly diagnosed patients, but, in general, no one should try to go from an A1c of 10% to 6% quickly. Take slow steps. Wanting to get to a “low” number very fast only causes harm. Diabetes is a long-term disease, so slow steps to establish new habits that can last a lifetime is the way to go. Anything too sudden and the body reacts badly.”

My perspective on A1c as a person living with diabetes

I have a very ambivalent relationship with my A1c myself. I’ve been living with type 1 diabetes for over 20 years, and my A1c is not something I think about in my daily life. However, every three months when I see my endo, I get a little anxious because receiving your A1c can feel a lot like getting your diabetes report card.

And, quite honestly, that’s really silly. My A1c number doesn’t reflect what’s been going on in my life for the last three months. It doesn’t tell me how much effort I’ve put into managing my diabetes and it does not define me as a person. It’s a good source of information, nothing more.

Still, we tend to look at it and judge, good or bad, how we’ve done with our diabetes management. But we really shouldn’t!

That doesn’t mean that I think we shouldn’t get our A1c checked. I absolutely think we should, but we also need to understand what it means as well as why we should look beyond the A1c number. I hope this guide has given you the knowledge and tools to do so!

About Christel Oerum

Christel is the founder of Diabetes Strong. She is a Certified Personal Trainer specializing in diabetes. As someone living with type 1 diabetes, Christel is particularly passionate about helping others with diabetes live active healthy lives. She’s a diabetes advocate, public speaker, and author of the popular diabetes book Fit With Diabetes.

Related Posts

Diabetes and Polyphagia (Excessive Hunger) One of the most challenging aspects of living with diabetes is that it can make you extra hungry for the one thing that affects your…

Symptoms of High Blood Sugar (Hyperglycemia) High blood sugars (hyperglycemia) can come on slowly or quickly depending on the type of diabetes you have and the cause of that particular high.…

Diabetes & Stress: How Stress Affects Your Blood Sugar Everyone experiences stress at some point in their lives. And stress can have a drastic effect on your blood sugar — both immediately and in…

Reader Interactions

Comments

- Peter says August 19, 2022 at 6:57 pm

Hi, I am 39 and my a1c was 6.9 and I reduced it to 5.5 in 3 months and lost weight from 160 pounds to 149 pounds by walking or running. Did I do anything wrong?

- Peter says August 19, 2022 at 6:58 pm

Sorry it was from 160 pounds to 120 pound. Peter again here

Christel Oerum says August 26, 2022 at 6:32 pm

Well done, sounds like you’re doing a lot of positive things for your health. Doesn’t sound like you did anything wrong, just remember to regularly check in with your doctor

I’m 67, 6’2″ and 205 pounds. Since having my first A1c test in December 2021 revealed a 6.7. I wasn’t going to let diabetes dictate my life so it wasn’t difficult to accept that I was going to make some serious changes. My second A1c test in April 2022 was 6.3 and my most recent A1c last week was 6.0…..crossing back into prediabetes. I’m happy.

Honestly, it’s become a challenge now that see how I can control my health with little effort resulting in significant change. I’m gonna continue improving until I’m within high 5 range.

If I can do it, so can others.

Hii I have diabetes from 14 years…My Hba1c test was 12% before a month and I had my DNC before a month ..can you please tell me how it is connected with my pregnancy and how many percent should my A1c percentage be before I plan fr my next pregnancy

- Christel Oerum says May 25, 2022 at 3:15 pm

Below you’ll find a few articles discussing diabetes and pregnancy. Considerations vary a bit depending on what type of diabetes you live with and how it’s treated so choose the article that’s relevant for you

Pregnancy and Type 1 Diabetes: Type https://diabetesstrong.com/pregnancy-and-diabetes/

Pregnancy with Type 2 Diabetes: https://diabetesstrong.com/pregnancy-type-2-diabetes/

Gestational Diabetes: https://diabetesstrong.com/gestational-diabetes/

I am a 66 yo male, very active, 5 feet 9 inches and 155 pounds. Resting heart rate is in the low 40s and the cardiologist told me to decrease the amount I exercise. A1C has been in the range of 5.9 to 6.1 for several years. Fasting blood sugars run from 90-100 -while after eating blood sugars are 90-110. A year ago, I was put on carb restrictions of 200 gm per day. I dropped 10 pounds in a few weeks and was hungry all the time. I added more carbs and gained about 5 pounds back. Recently my A1C increased to 6.3. My primary care physician advised me to do nothing and re-check the A1C in one year. I am not comfortable with this. My father had diabetes and had a major stroke at age 62 and died of a presumed heart attack at 67. Please advise.

- Christel Oerum says May 25, 2022 at 2:06 pm

If you’re uncomfortable with your doctor’s advice, you could get a second opinion, or push back on your doctor and ask him/her what the recommendation is based on. You don’t mention your diagnosis but an A1C of 6.3% is indicative of pre-diabetes and to put that into context the American Diabetes Association states that the goal for most adults with diabetes is an A1C that is less than 7%